Nara and Sake

Nara and Sake

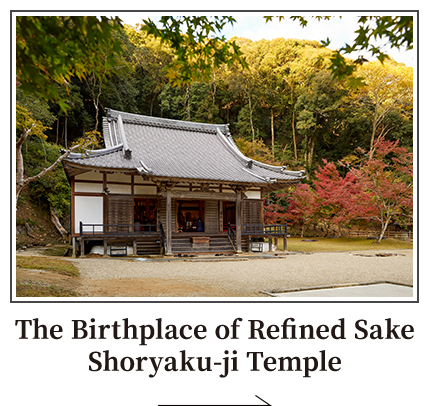

The Birthplace of Refined Sake Shoryaku-ji Temple

In the year 992, the high priest Kenshun erected Shoryaku-ji Temple following an order from Emperor Ichijo. It is apparent from a number of ancient texts that the temple was in fact the birthplace of refined sake. A section entitled “Bodaisen” in the record of sake Goshu no Nikki from the Muromachi period (1336–1573), for example, describes in detail the method of refined sake production at Shoryaku-ji Temple. The Tamonin Nikki, collated by successive orders of monks at Kohfuku-ji Temple from the end of the Muromachi period, also mentions sake brewing at Shoryaku-ji Temple, and morohaku-zukuri, a production method developed at Shoryaku-ji Temple, is believed to have formed the prototype of modern refined sake. In terms of dates, sake production appears to have flourished since the Kakitsu era (1441–1444) of the Muromachi period. There was said to be no finer sake than that of Shoryaku-ji Temple, and the ninth shogun of the Muromachi shogunate, Ashikaga Yoshihisa, gave it a ringing endorsement, saying that it was “simply the best.”

Financial circumstances led to refined sake being brewed at Shoryaku-ji Temple. At the time, the temple’s grounds were enormous, and vast amounts of the nation’s finances were being dedicated to supporting the livelihoods of the monks along with building upkeep costs and other expenses. However, the amount of money the temple was able to receive from the country became smaller and smaller, and Shoryaku-ji Temple was forced to secure its own funding. The price of refined sake at the time was high, and the temple was able to ensure a source of income through producing refined sake and selling it mainly to aristocratic and military families.

What made Shoryaku-ji Temple’s refined sake so special?

Before the production of refined sake began at Shoryaku-ji Temple, the alcohol of choice was nigori-zake, or unrefined sake. The ways the two are brewed are different, with the characteristics of refined sake being its sterilization with lactic-acid bacilli and the separation of yeast mash (large quantities of yeast which cause alcohol fermentation) and sake, a process which is carried out in stages several times. Furthermore, Shoryaku-ji Temple’s morohaku-zukuri involved using polished rice both for its koji malt and as the steamed rice used in brewing sake. This is how sterilized, safe sake was produced at Shoryaku-ji Temple. The power held by Shoryaku-ji Temple made it possible to produce sake in large yields, and preservation of the yeast mash ensured that the same product could be produced year after year. It was a revolution in the production of Japanese sake.

A seasonal specialty was also manufactured during summer (from around mid to late August) at Shoryaku-ji Temple, known as natsu-zake, literally meaning “summer sake.” Mold grows easily in the summer months, making the production of sake at other locations impossible. However, Shoryaku-ji Temple’s yeast mash Bodai-moto plays off the humidity and water quality, creating the potential for a miraculous summer sake. In a season when there were no other sakes on the market, natsu-zake became a sensation, favored by nobility for their moon-viewing parties and other occasions.

The Resurrection of Shoryaku-ji Temple’s Refined Sake

Although sake production at Shoryaku-ji Temple continued for roughly 200 years from the mid-fifteenth century Muromachi period (1336–1573), it eventually came to an end. Recent efforts to recreate Shoryaku-ji Temple’s refined sake began in 1996. The group responsible for these efforts is known as the Bodaimoto-focused Refined Sake Production Research Group of Nara Prefecture, and, with the help of the Nara Prefectural Institute of Industrial Development, they succeeded in harvesting the three kinds of bacteria required for sake production in the mountains of Shoryaku-ji Temple: lactic-acid bacilli, yeast fungus, and koji. After much investigative research, in 1998 the Bodai-moto method of sake production was reborn. Coinciding with this was the establishment of a number of basic criteria for Bodai-moto sake. These included stipulations that the yeast mash must be produced at Shoryaku-ji Temple, that Shoryaku-ji Temple yeast fungus must be used, and that rice and pure water from the temple’s grounds must also be used. In the same year, Shoryaku-ji Temple became the first temple in Japan to be granted a shubo license to produce the yeast mash used in sake, and production of the first run of Bodai-moto sake began in January 1999.

Nowadays there are eight companies producing Bodai-moto refined sake in Nara Prefecture, and they are even available for purchase at Shoryaku-ji’s Fukuju-in Temple. Sake from Nara is renowned for its flavor, and Bodai-moto refined sake’s characteristic full-bodied flavor is akin to white wine.

Source: Koushin Ohara, Chief Priest

Bodaisen, Shoryaku-ji Temple

Shoryaku-ji Temple’s Bodai-moto Sake Festival

Each year in early January, Shoryaku-ji Temple holds the Bodai-moto Sake Festival where yeast mash is prepared on the temple’s grounds. Members of the public can witness the process, sample and purchase newly released varieties, and participate in a rice-pounding event.

In recent years, Shoryaku-ji Temple has come to be known as the birthplace of Japanese refined sake, and it attracts constant visitors, even beyond the festival. Autumn is busy with sightseers, and the colorful autumn leaves are so beautiful they have even become the inspiration for extravagant kimono designs such as nishiki brocade.